Return to Home

Dropbox Search Operators

Helping Dropbox users retrieve content faster

Project overview

On the Search team at Dropbox, we were focused on how to enable our users to spend less time searching, and more time doing. We saw an opportunity to implement a highly-requested feature, so I sought to identify the real problem our users were facing, to see if and how it made sense to implement this feature.

The problem

Dropbox users frequently told us they couldn’t find what they were looking for—even when they knew the file existed.

One example:

“I’m trying to search for a multiword term like world trade center and Dropbox doesn’t allow phrase search. I get every result that has world or trade or center. It’s useless.”

For power users, the absence of search operators was a dealbreaker. Competitors like Evernote already supported Boolean search, wildcards, and filtering by file type. This gap wasn’t just frustrating—it was actively pushing users away.

But here’s the twist: while power users made up only 0.5% of our base, the underlying problem—wasting time sifting through irrelevant results—was universal.

Reframing the opportunity

When I looked closer, I realized the underlying problem wasn’t unique to power users. Most people don’t remember a file’s exact name. Instead, they remember one or two clues, like "It was a PDF," or "It was from last quarter."

Our current search didn’t support those mental models. The problem wasn’t just “we don’t have Boolean operators.” It was that users needed better ways to refine their queries and more confidence in their results.

This reframed our goal:

How might we help all users form better queries and get more relevant results, faster?

Research

To better understand the scope of the problem, I drew on three main inputs:

- Direct customer feedback: Hundreds of support tickets, forum posts, and user interviews highlighted the same frustrations. The language varied—from “Boolean operators” to “please let me filter by type”—but the need to refine results was consistent.

- Competitive analysis: Google Drive, Evernote, and Box all supported operators. Users noticed the gap and cited it as a reason Dropbox felt “behind.”

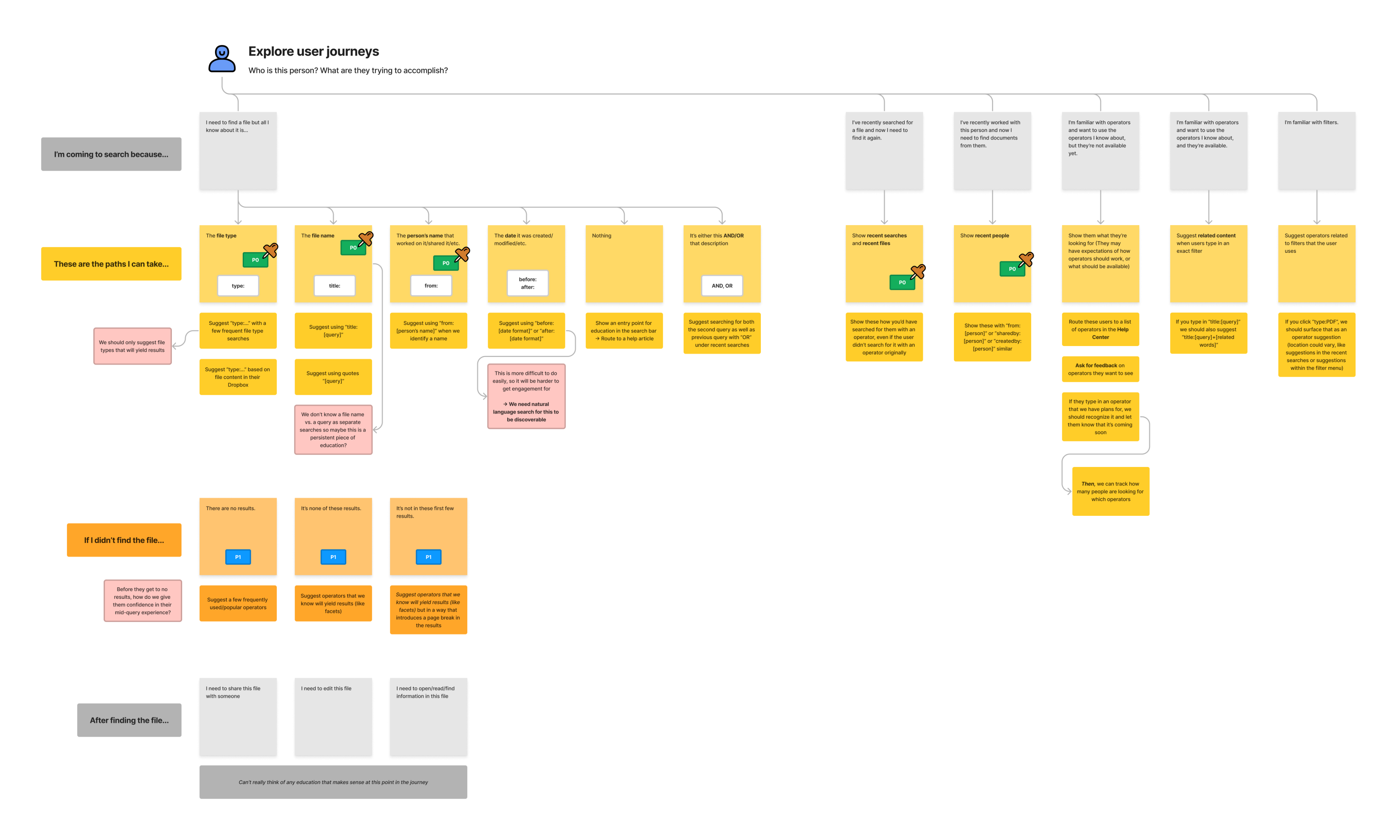

- User journey mapping: I synthesized scenarios from past research where users struggled in search. These often involved vague recall: remembering only one detail about the file. Mapping these journeys helped identify where operators could intervene—when typing in the search bar, when applying filters, and when validating results.

Key insights

Through feedback and scenario mapping, I saw that:

- Users often only remembered one clue about a file (its type, who shared it, when it was created).

- Education was as important as the functionality itself. Even if operators worked, users wouldn’t benefit unless they knew how to use them.

- The biggest barrier wasn’t capability—it was discoverability and validation. Users needed confidence that their query was recognized and applied.

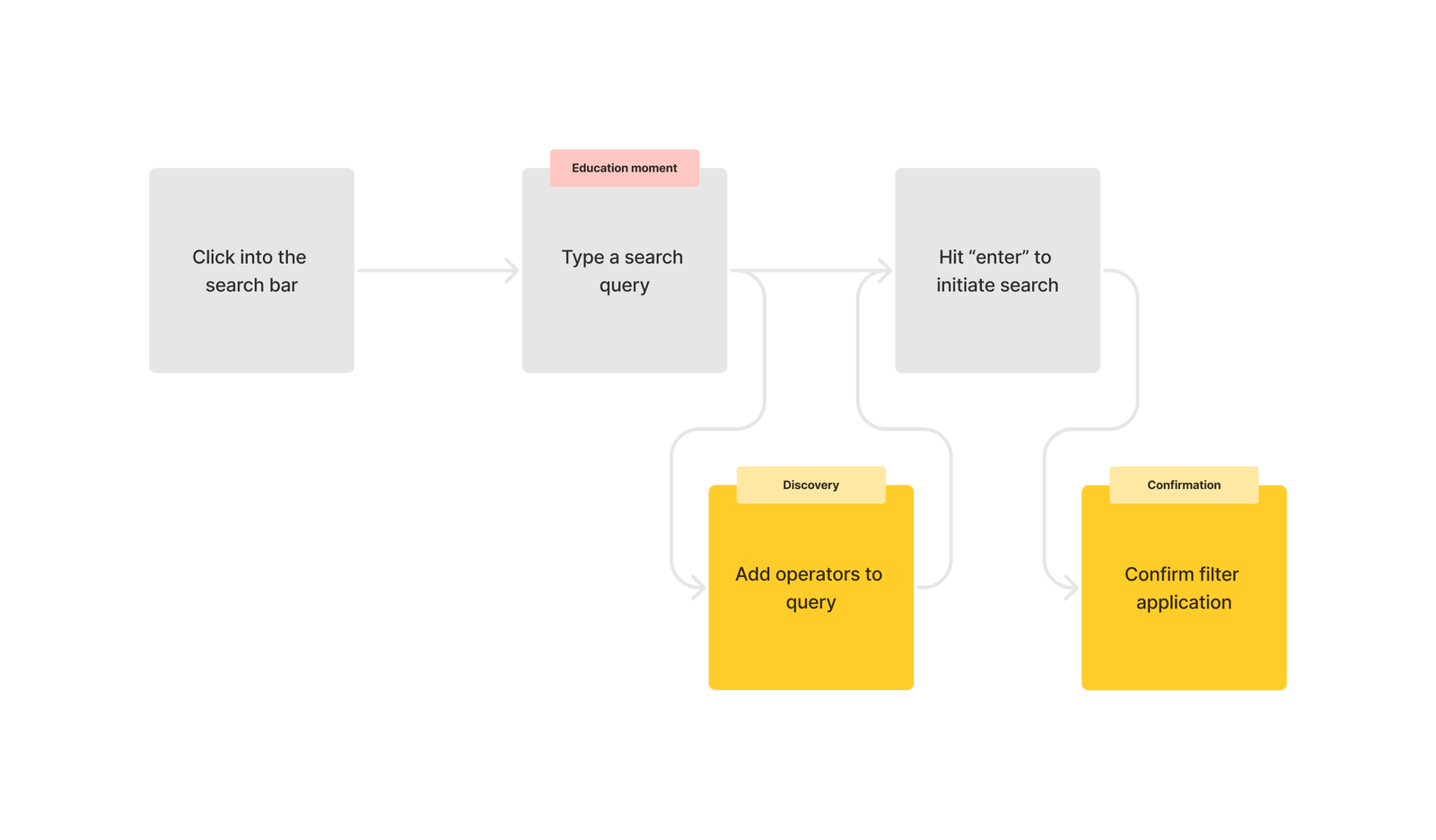

Discovery: Users need a way to find operators. The context of where they're found should help them understand how they work.

Confirmation: Users need to know that the operator was valid and applied. This should encourage users to continue to try and experiment with operators.

Design approach

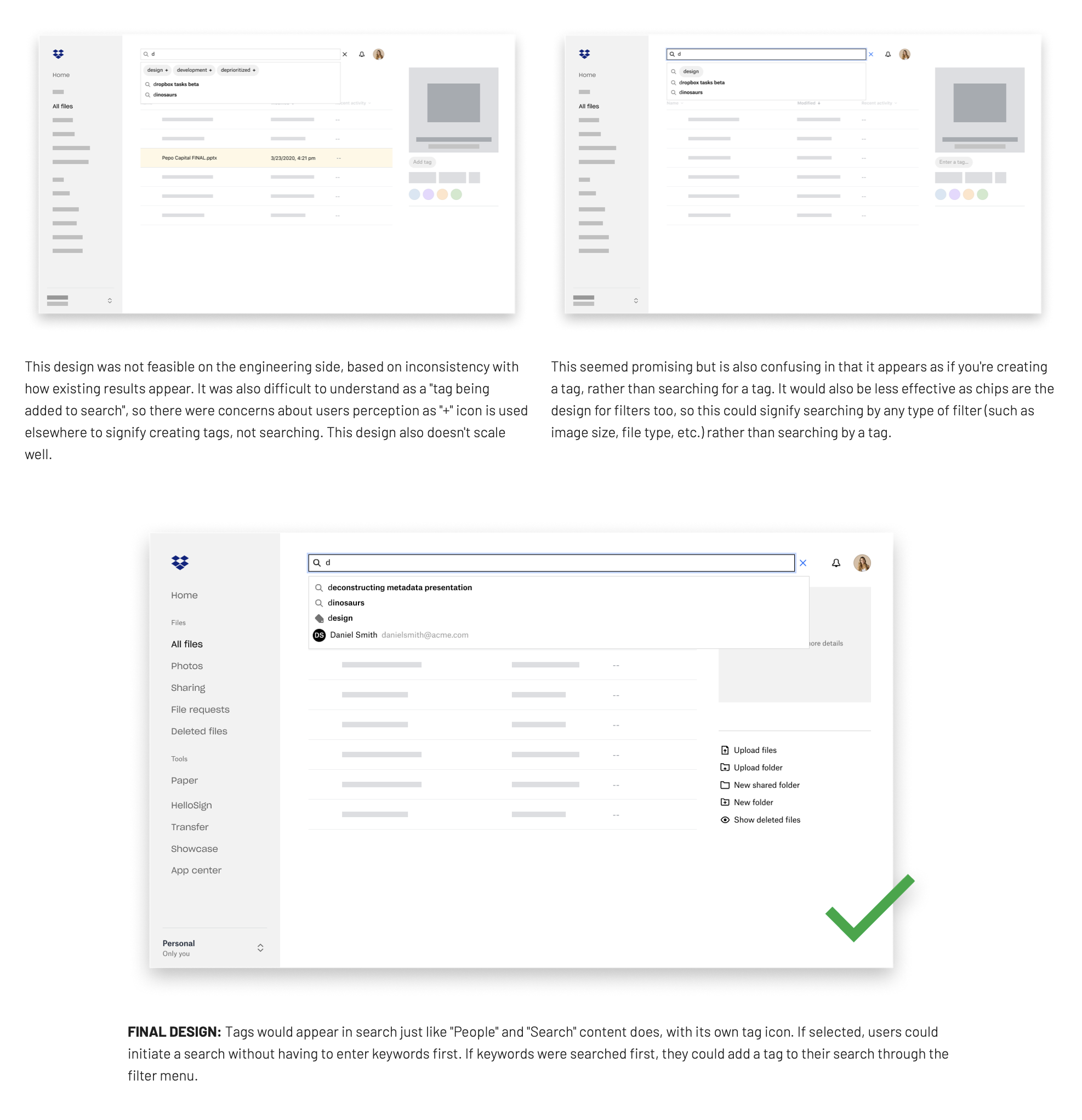

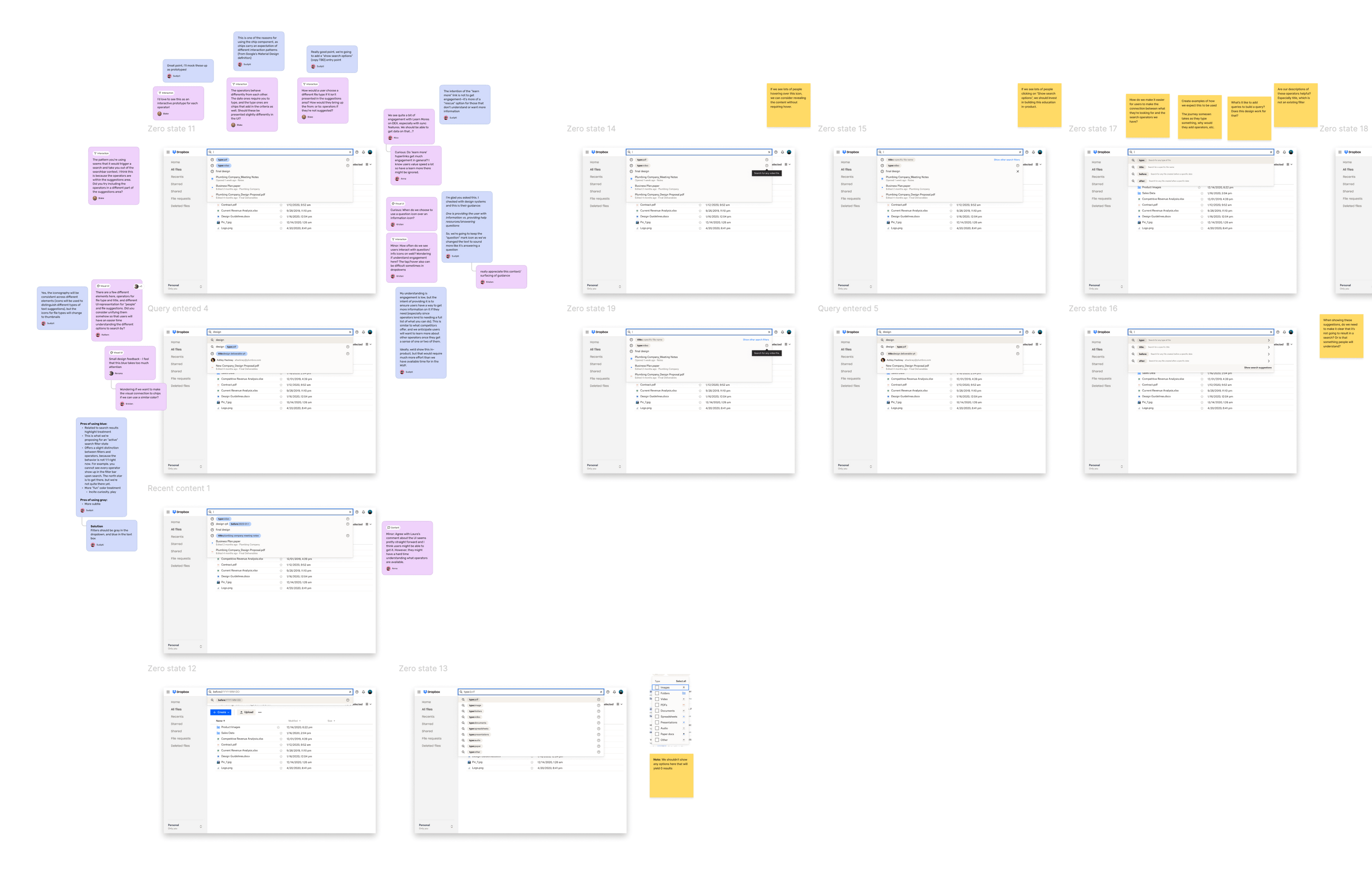

There’s a lot of smaller explorations that were done around the visual design, interaction design, and similar intricacies. I frequently took designs back to my larger crit group and local designers on my team to fine-tune the details. Since this design problem lended better to quantitative feedback, I chose to get user feedback through experimentation, which is why the final design was designed as multiple phases.

Some of the things I explored were:

- What’s the best way to visually imply a relationship between search operators and filters?

- What happens to the search bar when a person applies a filter?

- How does someone know that the search operator they typed was actually recognized/valid?

- What happens if a user changes a filter after entering a search operator that affects that filter?

The solution

To reduce risk and learn incrementally, I proposed a phased rollout:

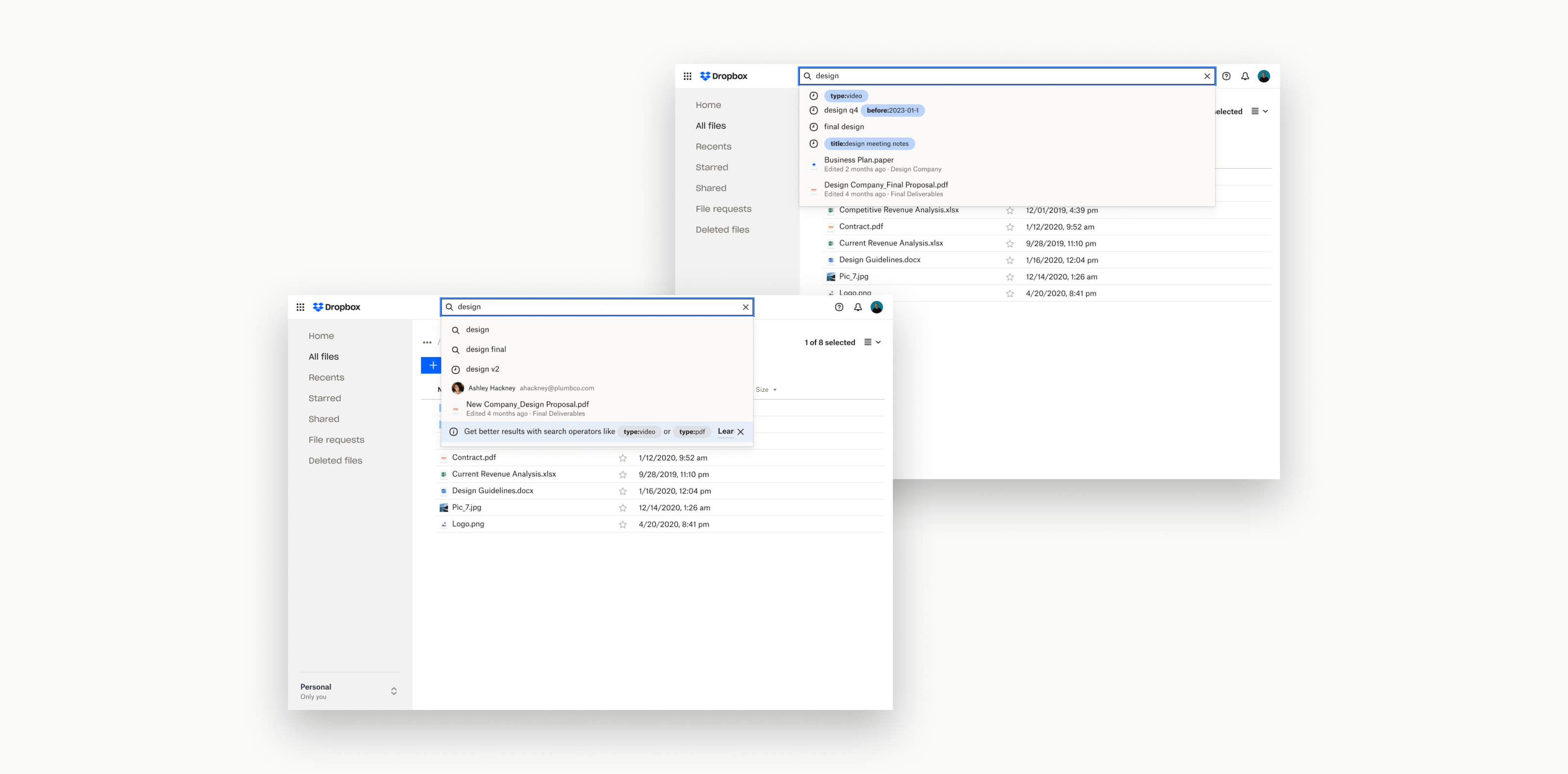

Phase 1: Introduce and validate

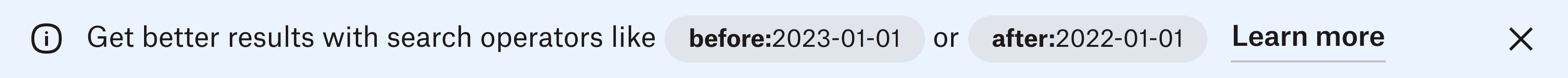

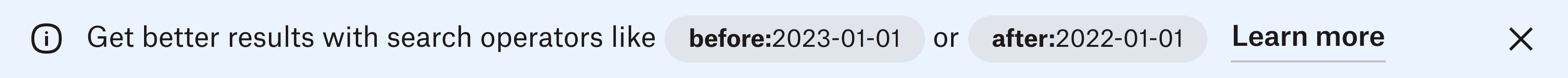

- Added a banner with operator examples like type:pdf or before:2023-01-01.

- When users applied a filter, we mirrored it as an operator in the search bar to reinforce the connection.

- Goal: validate whether operators improved time to success (finding and acting on the right file).

I’ll be the first to confess that a “learn more banner” is not my ideal design, but the goal in this first phase was not to gain adoption. The goal was to prove that for however many users decide to try it, that they actually are seeing an improvement in their “time to success”.

That being said, this phase was not completely devoid of user education. You’ll also see the operators, like “type:”, applied in your search bar when you select a filter. This was an effort to help users understand the relationship between the filters they’re accustomed to applying, and the new method of applying them through search operators.

Phase 2: Contextual education

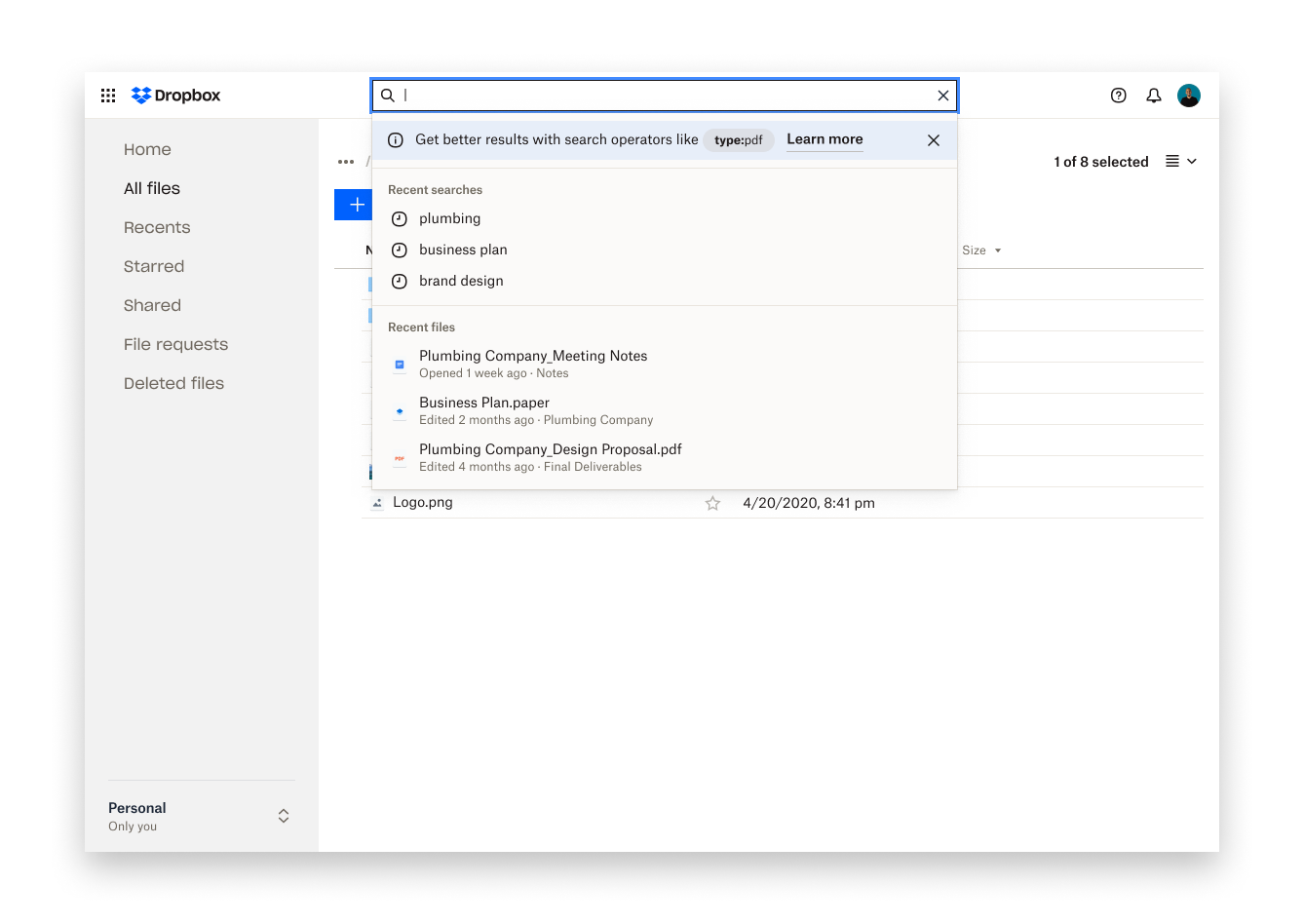

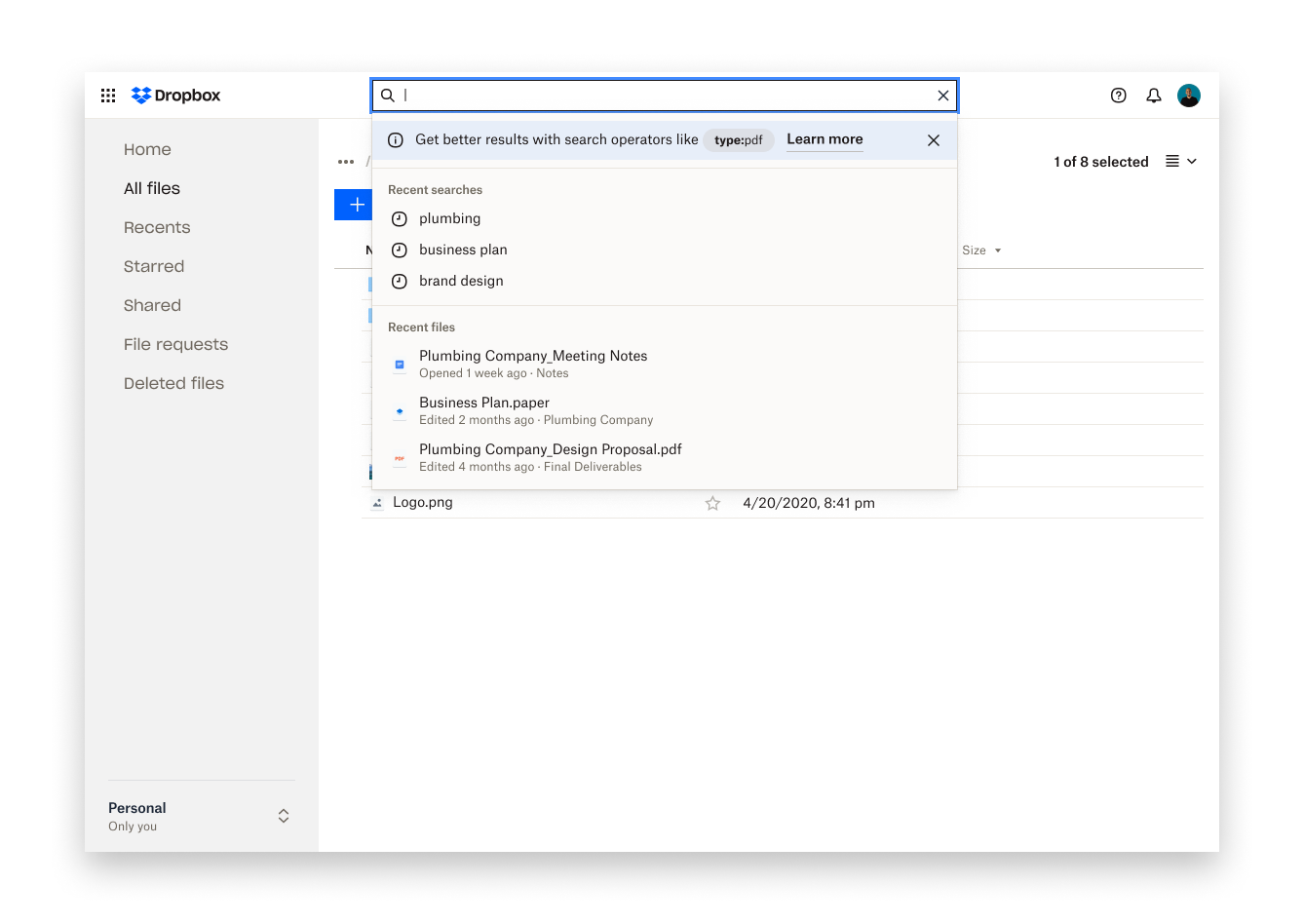

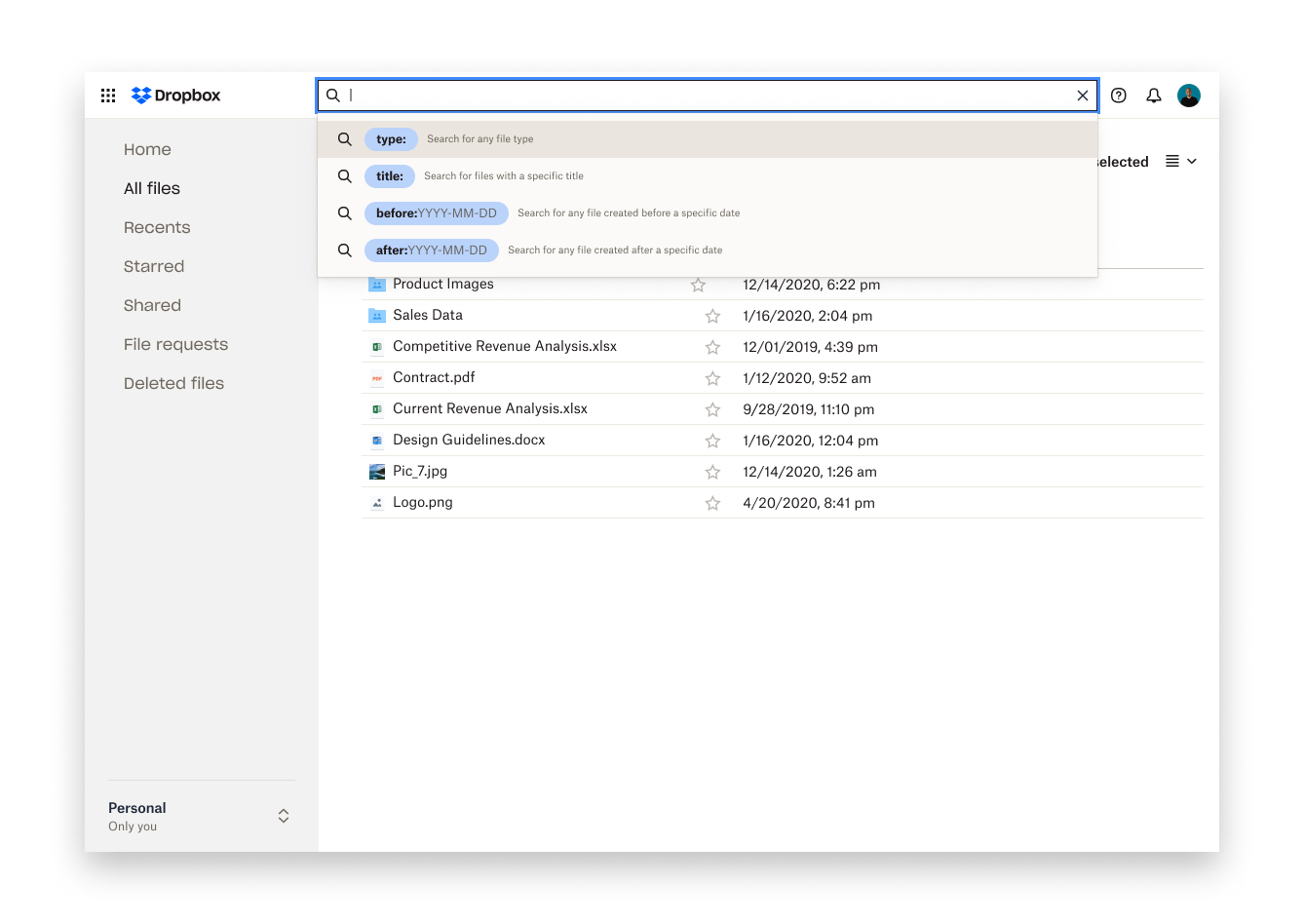

- Introduced operator suggestions in the empty state of the search bar.

- Added contextual hints as users typed queries, guiding them toward valid operators.

If we see success in the basic functionality of this design and can prove the value of the feature through Phase 1, we'll move forward to showing suggestions for each type of operator to see if we can increase usage of operators. We'll try this by showing examples in both the empty state of the search bar as well as contextually based on your search query.

Phase 3: North Star vision

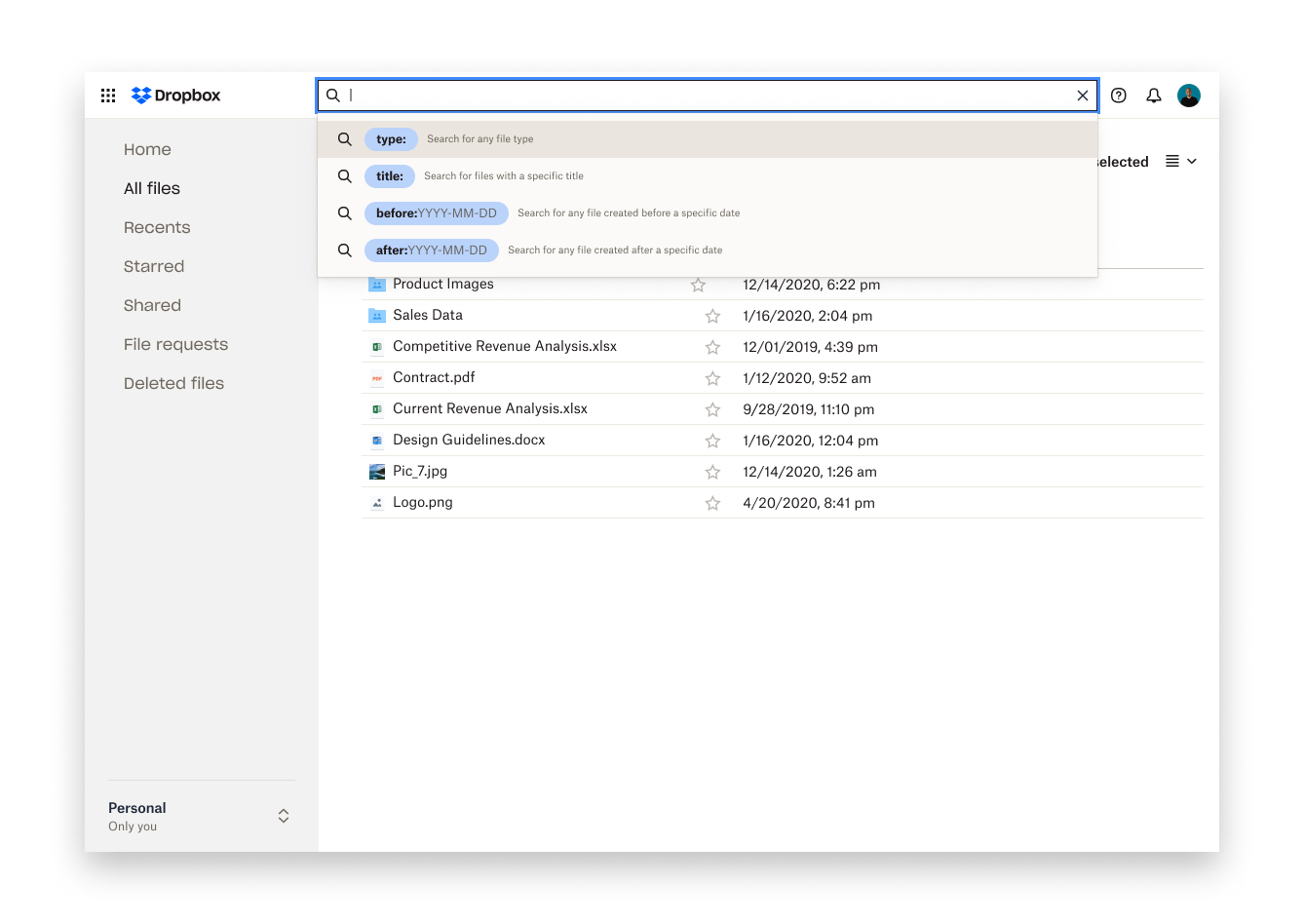

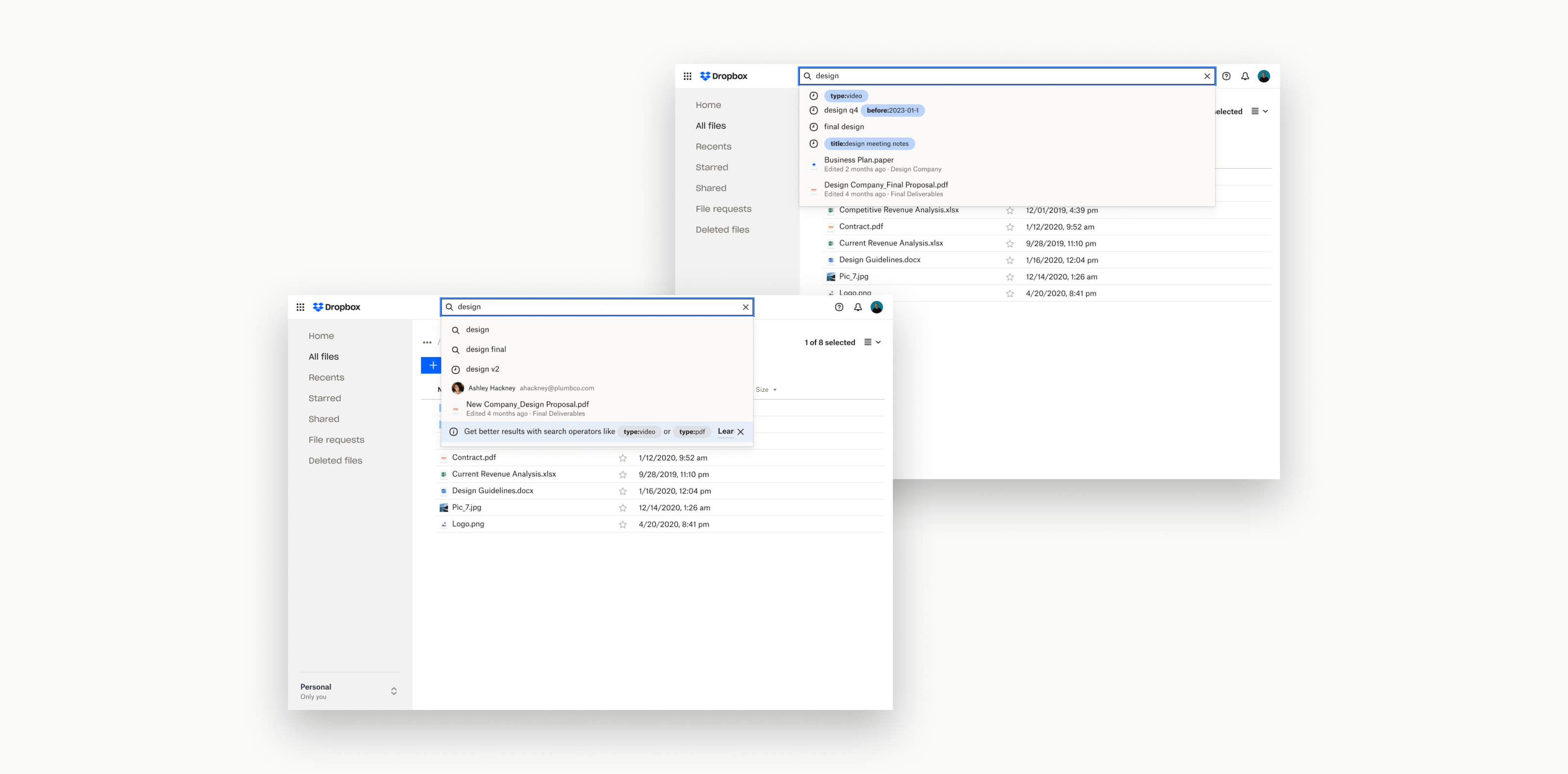

- A dynamic search bar that recognized operators as users typed, suggested refinements based on the query, and adapted based on recent searches.

- Goal: make operators feel like a natural part of search, not a hidden “advanced feature.”

Eventually, we'd like to dynamically update the typeahead results to show that we've identified a valid operator based on your search query. This was our North Star 💫—a future where operators are suggested based on how we’ve analyzed the potential search results of any query you’ve entered, or recent searches you’ve made.

Impact

Upon launching Phase 1 of this feature, we saw an average of 200-300k queries per day 🎉

As we work through the remaining phases, we also wanted to explore whether we saw an improvement in users’ time to success. We qualify "success" here as taking a qualified action, like editing or sharing the file. Before investing more heavily into education, we used the first phase of this design to gauge whether we see any improvement to the search experience for a small sample of users. If that test showed statistically significant results, we'd move forward to the next design to increase adoption of search operators (aka make operators discoverable to those we believe will benefit from them).

Reflection

This project started as a request to catch up with competitors. But by reframing the problem and grounding it in user research, we uncovered a broader opportunity: helping all users refine their queries and find what they need with confidence.

It also reinforced the importance of pairing functionality with education. Operators alone weren’t enough. Users needed contextual guidance, feedback, and validation to trust the system—and ultimately, to adopt a new way of searching.

Hey, there’s still more to see ↓

Dropbox Metadata

Helping teams organize content their own way

Return to Home

Dropbox Search Operators

Helping Dropbox users retrieve content faster

Project overview

On the Search team at Dropbox, we were focused on how to enable our users to spend less time searching, and more time doing. We saw an opportunity to implement a highly-requested feature, so I sought to identify the real problem our users were facing, to see if and how it made sense to implement this feature.

The problem

Dropbox users frequently told us they couldn’t find what they were looking for—even when they knew the file existed.

One example:

“I’m trying to search for a multiword term like world trade center and Dropbox doesn’t allow phrase search. I get every result that has world or trade or center. It’s useless.”

For power users, the absence of search operators was a dealbreaker. Competitors like Evernote already supported Boolean search, wildcards, and filtering by file type. This gap wasn’t just frustrating—it was actively pushing users away.

But here’s the twist: while power users made up only 0.5% of our base, the underlying problem—wasting time sifting through irrelevant results—was universal.

Reframing the opportunity

When I looked closer, I realized the underlying problem wasn’t unique to power users. Most people don’t remember a file’s exact name. Instead, they remember one or two clues, like "It was a PDF," or "It was from last quarter."

Our current search didn’t support those mental models. The problem wasn’t just “we don’t have Boolean operators.” It was that users needed better ways to refine their queries and more confidence in their results.

This reframed our goal:

How might we help all users form better queries and get more relevant results, faster?

Research

To better understand the scope of the problem, I drew on three main inputs:

- Direct customer feedback: Hundreds of support tickets, forum posts, and user interviews highlighted the same frustrations. The language varied—from “Boolean operators” to “please let me filter by type”—but the need to refine results was consistent.

- Competitive analysis: Google Drive, Evernote, and Box all supported operators. Users noticed the gap and cited it as a reason Dropbox felt “behind.”

- User journey mapping: I synthesized scenarios from past research where users struggled in search. These often involved vague recall: remembering only one detail about the file. Mapping these journeys helped identify where operators could intervene—when typing in the search bar, when applying filters, and when validating results.

Key insights

Through feedback and scenario mapping, I saw that:

- Users often only remembered one clue about a file (its type, who shared it, when it was created).

- Education was as important as the functionality itself. Even if operators worked, users wouldn’t benefit unless they knew how to use them.

- The biggest barrier wasn’t capability—it was discoverability and validation. Users needed confidence that their query was recognized and applied.

Discovery: Users need a way to find operators. The context of where they're found should help them understand how they work.

Confirmation: Users need to know that the operator was valid and applied. This should encourage users to continue to try and experiment with operators.

Design approach

There’s a lot of smaller explorations that were done around the visual design, interaction design, and similar intricacies. I frequently took designs back to my larger crit group and local designers on my team to fine-tune the details. Since this design problem lended better to quantitative feedback, I chose to get user feedback through experimentation, which is why the final design was designed as multiple phases.

Some of the things I explored were:

- What’s the best way to visually imply a relationship between search operators and filters?

- What happens to the search bar when a person applies a filter?

- How does someone know that the search operator they typed was actually recognized/valid?

- What happens if a user changes a filter after entering a search operator that affects that filter?

The solution

To reduce risk and learn incrementally, I proposed a phased rollout:

Phase 1: Introduce and validate

- Added a banner with operator examples like type:pdf or before:2023-01-01.

- When users applied a filter, we mirrored it as an operator in the search bar to reinforce the connection.

- Goal: validate whether operators improved time to success (finding and acting on the right file).

I’ll be the first to confess that a “learn more banner” is not my ideal design, but the goal in this first phase was not to gain adoption. The goal was to prove that for however many users decide to try it, that they actually are seeing an improvement in their “time to success”.

That being said, this phase was not completely devoid of user education. You’ll also see the operators, like “type:”, applied in your search bar when you select a filter. This was an effort to help users understand the relationship between the filters they’re accustomed to applying, and the new method of applying them through search operators.

Phase 2: Contextual education

- Introduced operator suggestions in the empty state of the search bar.

- Added contextual hints as users typed queries, guiding them toward valid operators.

If we see success in the basic functionality of this design and can prove the value of the feature through Phase 1, we'll move forward to showing suggestions for each type of operator to see if we can increase usage of operators. We'll try this by showing examples in both the empty state of the search bar as well as contextually based on your search query.

Phase 3: North Star vision

- A dynamic search bar that recognized operators as users typed, suggested refinements based on the query, and adapted based on recent searches.

- Goal: make operators feel like a natural part of search, not a hidden “advanced feature.”

Eventually, we'd like to dynamically update the typeahead results to show that we've identified a valid operator based on your search query. This was our North Star 💫—a future where operators are suggested based on how we’ve analyzed the potential search results of any query you’ve entered, or recent searches you’ve made.

Impact

Upon launching Phase 1 of this feature, we saw an average of 200-300k queries per day 🎉

As we work through the remaining phases, we also wanted to explore whether we saw an improvement in users’ time to success. We qualify "success" here as taking a qualified action, like editing or sharing the file. Before investing more heavily into education, we used the first phase of this design to gauge whether we see any improvement to the search experience for a small sample of users. If that test showed statistically significant results, we'd move forward to the next design to increase adoption of search operators (aka make operators discoverable to those we believe will benefit from them).

Reflection

This project started as a request to catch up with competitors. But by reframing the problem and grounding it in user research, we uncovered a broader opportunity: helping all users refine their queries and find what they need with confidence.

It also reinforced the importance of pairing functionality with education. Operators alone weren’t enough. Users needed contextual guidance, feedback, and validation to trust the system—and ultimately, to adopt a new way of searching.

Hey, there’s still more to see ↓

Dropbox Metadata

Helping teams organize content their own way